Ocean economy is valuable: Generates trillions in annual value, supports livelihoods, and underpins global food, energy, and climate systems. Financial losses from degradation are substantial.

Ocean as an investment class:

- Investment should combine financial purpose and elegance.

- ESG and sustainable outcomes drive investor interest.

- Recovery projects (artificial reefs, blue carbon, marine protected areas) can be bankable assets.

What investors want:

- Protect supply chains, assets, and reputation.

- Clear ROI via ecosystem service payments or scalable solutions.

- Strong leadership teams, credible markets, and reliable data.

- Simplicity in execution; complexity hidden behind intuitive metrics.

Methods to mobilise capital:

- Private sector investment, blue bonds, overseas grants.

- Early-stage de-risking, positive nature interventions (e.g., seabed leasing, oyster reefs).

- Utilise compensation funds from renewable energy projects.

- Policy levers: remove subsidies, levy fossil fuels, charge tourism/shipping fees.

Measuring marine environments:

- Modern tools: UAVs, ROVs, AI/deep learning, eDNA, 3D structural complexity.

- Metrics: Mean species abundance, potential for loss, ecosystem services.

- Standardisation and disclosure: TNFD, ENCORE, DPSIR frameworks.

- Translate science into investor-friendly formats to reduce risk and guide action.

Philanthropy vs ocean economy:

- Philanthropy: ROI defined by principles, dependent on goodwill, limited scale.

- Ocean economy: embeds sustainability into financial systems, generates measurable ROI, professional workforce, community participation.

- Actionable finance needed to match or exceed the scale of subsidies and global impacts.

Where next:

- Focus on direction, execution, and scalability, not just funding or ambition.

- Use existing mechanisms and imperfect metrics to act now.

- Early adoption gives corporations competitive advantage.

- Replicability and professionalisation are key to systemic transformation.

Hosted at the Royal Geographic Society, London in September 2025, Blue Finance 2025, outlined a future of sustainable ocean recovery through well-directed collaborations between the finance sector, governments, science and industry. This was more than just a policy discussion, it was positioned as a strategic opportunity to shape and invest in sustainable economic growth centred around the value of the marine environment.

The ocean economy, estimated to be worth over $2.5 trillion annually, remains a critical yet increasingly vulnerable asset. Climate change, overfishing, pollution and coastal degradation continue to place enormous pressure on marine ecosystems. The conference showcased emerging solutions from the financial and investment sectors, from nature-based approaches and blue carbon initiatives to marine technology innovations and data-driven conservation models.

Throughout the event, discussions focused on some of the most pressing challenges facing the blue finance sector: how to align investment with credible environmental outcomes; how to measure and report the real-world impact of ocean-related finance; and how to ensure that benefits reach local communities and frontline stakeholders.

For companies working across Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) strategy, sustainable investment and supply chain resilience, Blue Finance 2025 offered a platform to connect with researchers, investors and project developers building the tools, metrics and technologies that can make blue finance viable. One area of particular interest was the role of marine technology in improving the quality and transparency of ocean data, crucial for understanding investment risk and building trust in environmental claims.

Like many of the attendees, my background is in marine conservation and technology not finance and investment; however, the talks were inspirational and showed a clear trajectory for scalable and sustainable ocean conservation that doesn’t rely on charity but rather an understanding that the ocean provides valuable services that must be protected and should be invested in. In my summary of the conference, I have tried to group the panel comments, presenter slides and QA information around key themes. If readers find inaccuracies or incorrect attributions, please get in contact so I can correct them.

Why the ocean economy matters

The ocean economy matters to the finance sector because it is both large in scale and intrinsically tied to global economic flow. The ocean has been valued as an asset at roughly US$24 trillion, and the annual flow of goods and services from coastal and oceanic environments is estimated at about US$2.5 trillion — a stream of provisioning, regulating and cultural services that feeds shipping, fisheries, tourism, coastal protection and more. These are not abstract ecological benefits: they are recurring economic returns and capital values that sit squarely in the remit of asset owners and portfolio managers.

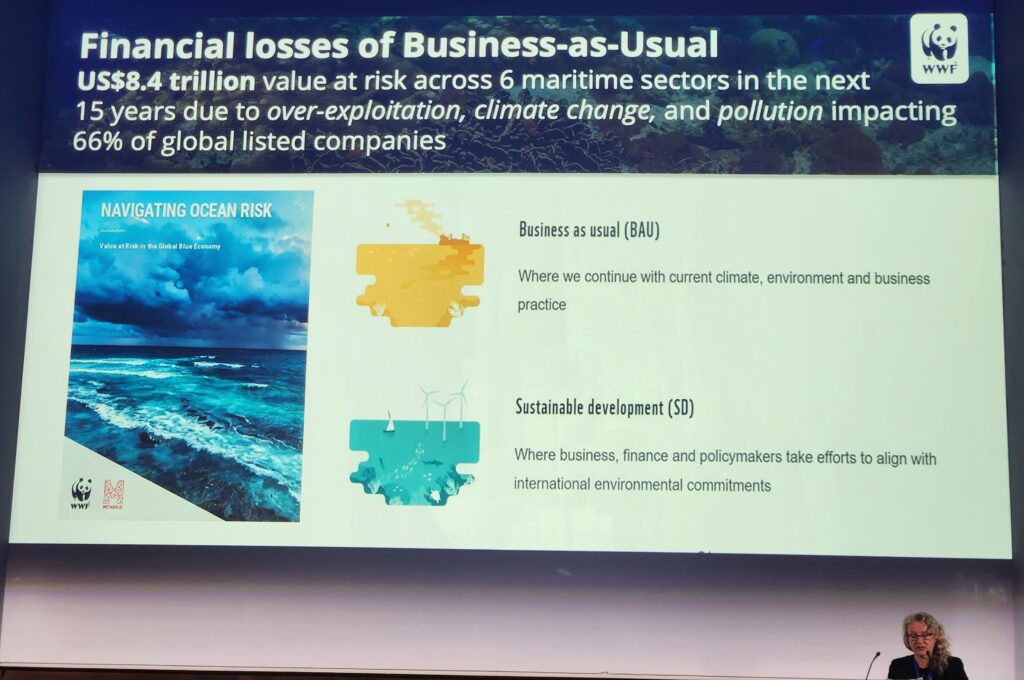

Continuing on a “business as usual” trajectory exposes a massive portion of that value to loss. WWF’s analysis highlights that roughly US$8.4 trillion of value is at risk across six maritime sectors over the next 15 years because of over-exploitation, climate change and pollution — and these risks extend into the balance sheets of listed companies and the portfolios that own them. Put bluntly: unmanaged ocean decline translates into direct, measurable financial downside for investors and lenders. This risk-to-value asymmetry is a clear motivation for the financial sector to reallocate capital toward resilience and sustainability.

That opportunity is not only about preventing losses; it’s also about redirecting capital to solutions with material climate and socioeconomic returns. Recent ocean finance assessments argue that by 2030 around US$1 trillion of finance could be targeted at ocean-based climate solutions, and that mobilising those flows — through blended finance, domestic resource mobilisation and de-risking mechanisms — is essential for coastal resilience, clean energy and marine ecosystem restoration. For investors, this means developing asset classes and strategies (blue bonds, nature-based project finance, sustainable aquaculture, offshore renewables) that can deliver both impact and differentiated return streams as markets price in sustainability.

Linking environmental decline to financial outcomes is no longer hypothetical. High-profile case studies collected by market analysts show substantial, quantifiable financial impacts from nature-related shocks — everything from steep falls in market cap to credit downgrades and expensive litigation — demonstrating the direct channels by which nature loss becomes investor losses. This is the logic behind the growing mantra in the risk world: “nature risk is financial risk.” For asset allocators, integrating nature-related exposures is therefore not just ESG virtue-signalling but core prudential risk management.

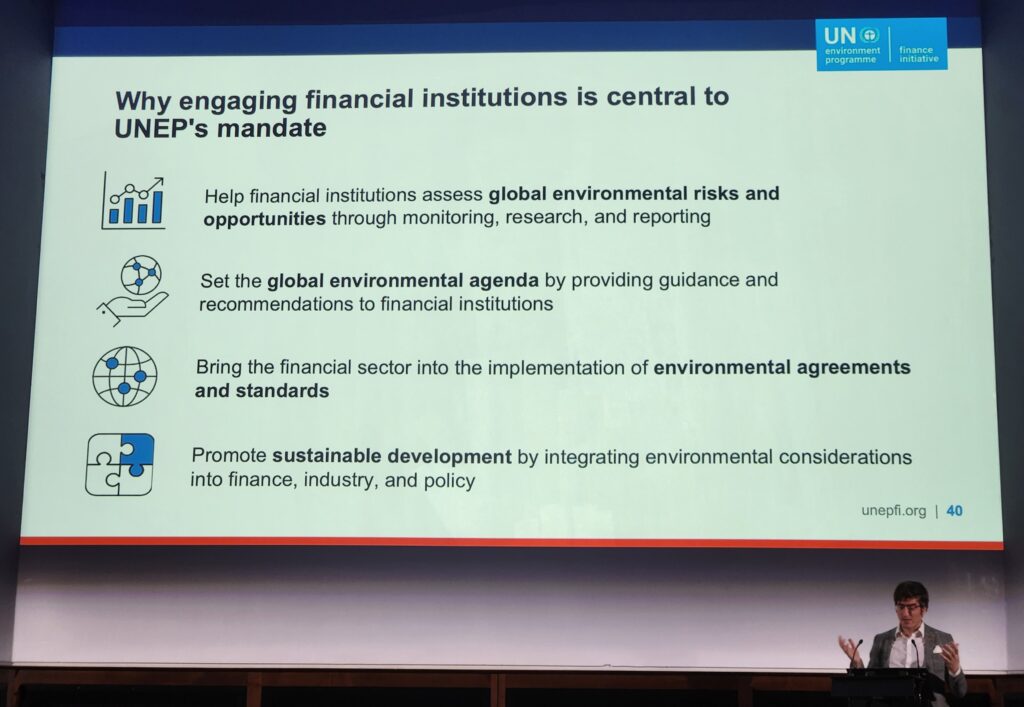

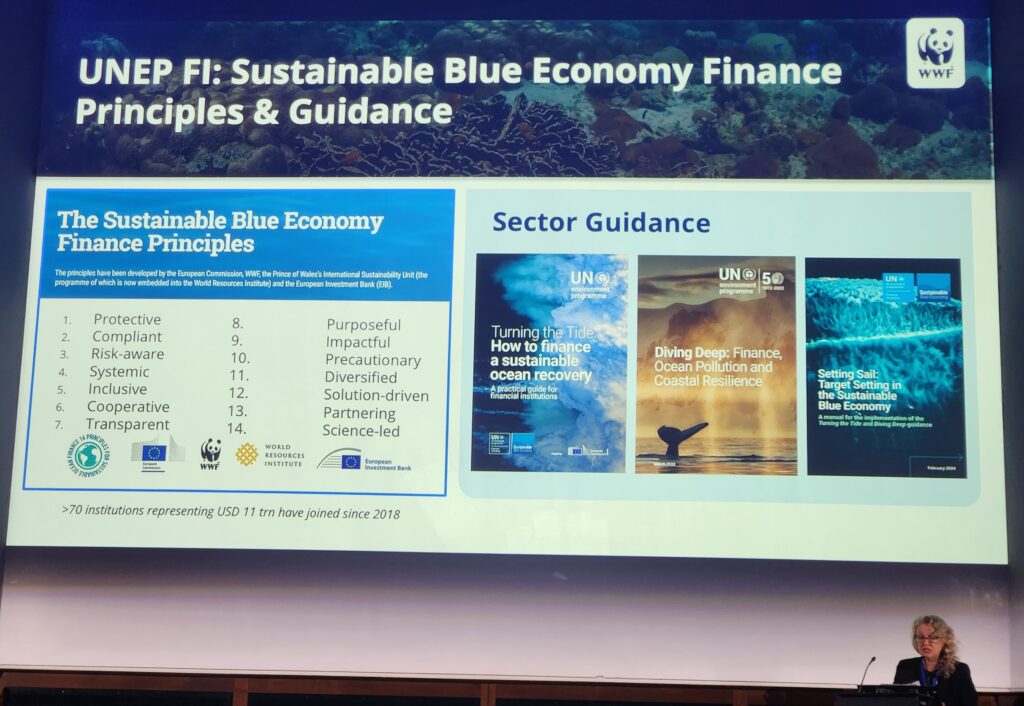

There is also a governance and systems reason for finance to engage: the global finance architecture is already mobilising to align capital with planetary limits. Initiatives such as the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative mobilise a global network of banks, insurers and investors to catalyse action — offering guidance, tools and policy engagement that help integrate nature and climate into mainstream financial decision-making. For institutional investors, participating in these efforts reduces transition uncertainty, shapes emerging regulatory standards, and creates market-level incentives to internalise ocean sustainability into valuation and stewardship practices. In short, the ocean economy is both a set of valuable assets and a source of systemic risk — a combination that makes it a high-priority arena for informed investment.

The ocean as an investment asset class

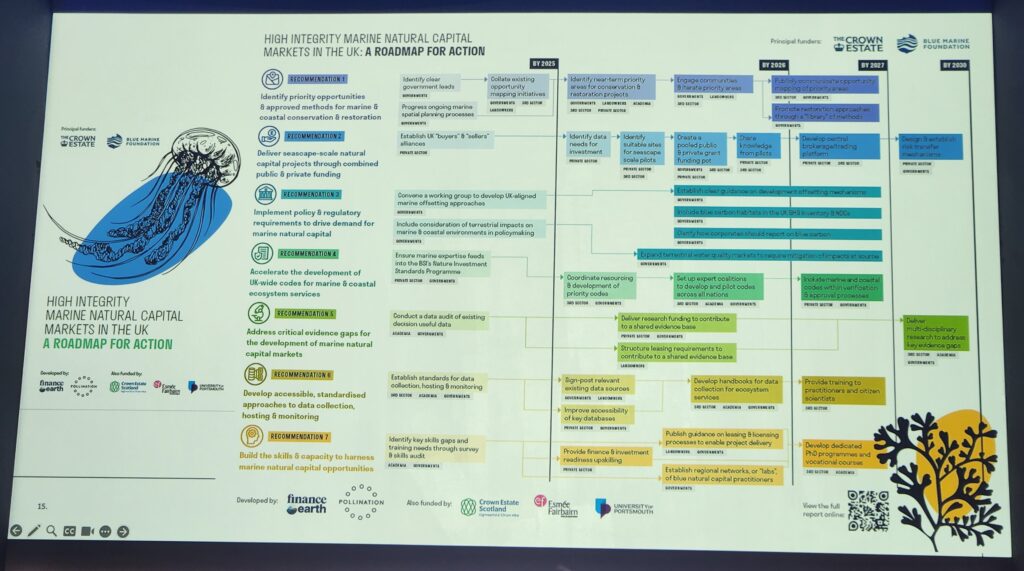

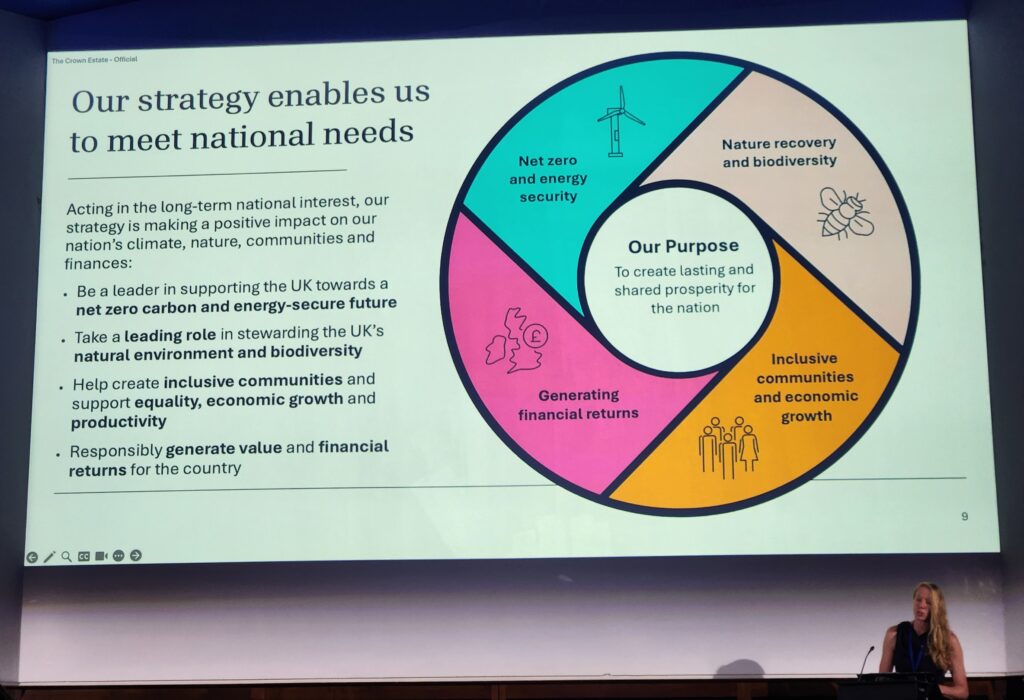

The scale and urgency of the “blue acceleration” — the rapid expansion of ocean industries from aquaculture to offshore energy and seabed infrastructure — underscores the need for a more structured, forward-looking approach to ocean investment. Caroline Price, Head of Nature & Environment (Marine) at The Crown Estate, emphasised the importance of a clear strategy and roadmap for ocean finance. This means designing investment pathways that are not just reactive to environmental crises but proactively position the ocean as a central arena for sustainable economic growth.

A central part of this positioning comes from the risk side of finance. As Gerrit Sindermann, Executive Director of the Green Digital Finance Alliance, notes, investment is often channelled through risk mitigation in ESG frameworks. If ocean decline is a systemic risk — threatening industries, supply chains, and financial stability — then investing in ocean recovery and conservation becomes a rational, defensive allocation. This perspective reframes conservation and sustainable use as essential hedges against material environmental, social, and governance risks.

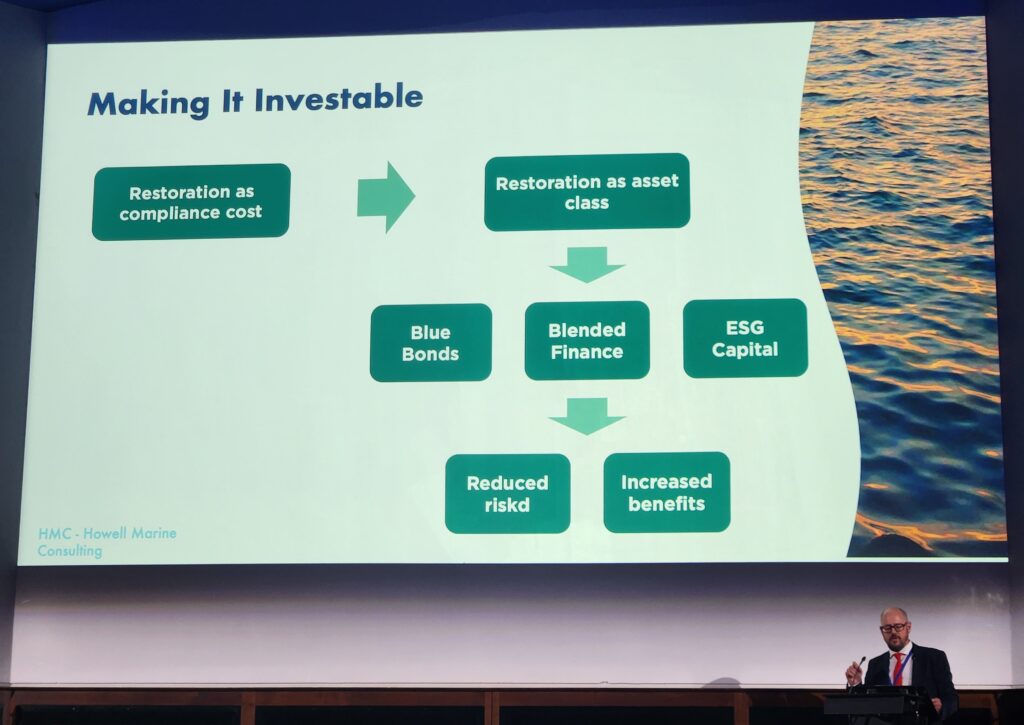

Beyond risk management, leaders in the field argue for recognition of the ocean as a positive investment class in its own right. Dickon Howell, CEO of Howell Marine Consulting, is explicit: ocean recovery should be seen as an investment class asset. Like infrastructure or real estate, a sustainable ocean economy generates long-term, tangible returns — from fisheries and tourism to renewable energy and carbon sequestration. But for capital to flow, the sector must be “made investable” through clear frameworks, standards, and vehicles.

Torsten Thiele, Founder of the Global Ocean Trust, added a further dimension: purpose. He argues that “finance with a purpose” is not a neutral force but a driver targeted towards outcomes. For the ocean, this means steering capital deliberately toward resilience, biodiversity, and climate solutions — aligning financial returns with planetary health. Thiele also introduced the concept of “financial elegance”: achieving financial goals with minimal effort and cost. In his view, the ocean can and should be an investment class that combines financial purpose with financial elegance, enabling markets to meet Sustainable Development Goals while delivering efficient, effective returns.

These perspectives align with broader global efforts. UNEP’s leadership on sustainable finance has highlighted the importance of collaboration, standard-setting, and measurable outcomes in ocean-related investment. As Klaas de Vos of Ocean Fox Advisory points out, measurement is crucial — investors will only commit if they can reliably track impact, risk, and return. This was explored in more detail in the session on Day 2, sharing examples of how initiatives must be structured, transparent, and scalable to unlock institutional capital.

Taken together, these insights point toward a reframing: the ocean is not simply a resource base to be protected, nor only a sectoral risk factor to be managed. It is emerging as a distinct investment class — a portfolio of opportunities where financial capital and natural capital meet. With the right roadmaps, risk frameworks, investable vehicles, and purposeful finance, the ocean economy can become a cornerstone of sustainable global investment.

What investors want from ocean investment

For investors, the motivation to engage in the ocean economy stems from both necessity and opportunity. As Louise Heaps, Global Lead on Sustainable Blue Economy at WWF, explains, corporate investors are driven by a mix of protecting supply chains, safeguarding assets, and ethical commitments. Offshore windfarms, for example, are not only revenue-generating energy projects but also a demonstration of climate responsibility. Similarly, blue carbon projects and nature-inclusive design are valued as both protective measures against flood and storm damage and as reputational assets in a competitive “race to the top” for sustainability leadership.

At the core, however, investors need clarity on return on investment. “When someone pays for an ecosystem service, this is the ROI,” stresses Eoin Murray, CIO of Rebalance Earth. This highlights the need for robust government codes and trusted data frameworks that translate ecosystem services — such as carbon sequestration by mangroves or coastal protection by reefs — into measurable, tradable, and bankable financial flows. Without this codification, ecosystem services remain a theoretical value rather than a tangible income stream.

The private equity perspective is more blunt. As Ed Phillips, Managing Director of Future Planet Capital, observes, investors understand that perhaps only one in ten ventures may generate significant ROI. Investment decisions are therefore grounded in three important criteria: the strength of the founders and leadership; the clarity of who will pay for the solution (because, as Phillips notes, “the ocean itself cannot pay”); and whether the product or service can scale beyond pilot projects into robust markets. High risk can be acceptable — provided there is proportional potential for returns and a pathway to scalability.

A recurring theme is the role of data. Kirsty Schneeberger, Founder & CEO of Athena Blue, argues that data gaps remain the biggest barrier to investor confidence and funding. Investors will not commit to ocean recovery at scale unless they can access reliable metrics that quantify risks, validate business models, and track performance. This sentiment is echoed in investment roadmaps which stress that measurement is foundational — a principle reinforced by the FAIRR Initiative’s analysis of why investors are pivoting toward sustainability.

Robust data is vital but the pathway to execution must be simple. As Klaas de Vos, Founder of Ocean Fox Advisory, puts it: “Private sector execution lies in simplicity.” Caroline Price of The Crown Estate also warns that complexity will stifle progress — an important reminder that although the ocean is a highly complex system, investment mechanisms must be accessible, transparent, and intuitive. The challenge, then, is to translate ecological and systemic complexity into streamlined, user-friendly tools for investors.

Concepts from books focused on user experience design such as Simplexity (Kluger, 2008) and No Straight Lines (Moore, 2011) offer useful metaphors. Both works argue that the apparent simplicity of effective systems often conceals deep structural complexity. The task for ocean finance is similar: to design frameworks that make investment decisions straightforward, while embedding the sophisticated science, governance, and risk management required behind the scenes. In other words, complexity is not eliminated, but hidden in ways that allow capital to flow efficiently.

In summary, investors want three things from ocean investment: clear motivation (protecting assets, supply chains, and reputation), bankable returns (defined through ecosystem service payments, scalable business models, and credible ROI expectations), and confidence (delivered by trusted data and simple, executable mechanisms). Delivering on these expectations is essential if the ocean economy is to develop as an investable class.

Methods of investment in the ocean and mobilising capital

Mobilising capital into the ocean economy requires mechanisms that are both credible for investors and effective in delivering measurable outcomes. The trajectory of ocean finance, as highlighted in recent analysis, shows a gradual but accelerating shift from grant-based models toward blended finance, bonds, and private sector instruments. The challenge now is to structure pathways that de-risk early investment, create stable revenue streams, and make projects investable at scale.

One lesson comes from the energy sector. As Eoin Murray, CIO of Rebalance Earth, argues, governments should treat nature recovery today like they treated wind power 20 years ago. Early-stage renewable energy only became investable once governments guaranteed a price floor for power generation; a similar approach could guarantee outcomes in ecosystem services, giving investors confidence to enter early markets such as blue carbon, reef restoration, or coastal protection.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) also illustrate how finance and conservation can converge. Louise Heaps of WWF notes that MPAs should be seen not only as conservation tools but also as a way of protecting investments — ensuring that marine natural capital underpinning fisheries, tourism, and infrastructure is preserved for the long term. This framing positions protected areas as financial safeguards, rather than just ecological commitments.

At a more structural level, Daniel Wilde, Head of Oceans at the Commonwealth Secretariat, identified three main methods of ocean investment. First, private sector investment, which faces challenges including political risk, exchange rate volatility, limited capacity to generate bankable projects, and restricted access to revenue streams. Second, island-scale funding instruments such as blue bonds, which have already demonstrated their potential to unlock national-scale conservation finance. And third, overseas grant funding, which continues to play a vital role in seeding projects and supporting ocean-focused initiatives where market mechanisms are not yet mature.

An example of this is the Seychelles’ Blue Bond, the world’s first sovereign blue bond launched in 2018. Backed by the World Bank and the Global Environment Facility, it raised US$15 million to support sustainable fisheries and marine conservation. By blending concessional finance with market capital, Seychelles created a replicable model for other island and coastal states, showing how innovative debt instruments can unlock funding for long-term ocean stewardship while strengthening local economies.

Practical interventions can also shift risk-reward profiles. Dickon Howell, CEO of Howell Marine Consulting, stresses the need to embed positive nature interventions at the earliest stages of planning, such as in seabed leasing frameworks. This ensures that biodiversity and resilience are factored in before projects reach execution. Similarly, George Birch, Founder of Oyster Heaven, highlights the concept of “selling de-risking assets”: deploying natural infrastructure like oyster reefs to stabilise fish stocks, protect coastlines, and reduce financial exposure for fisheries and coastal economies.

Compensation and offsets also provide a funding stream. Sarah Brown, Fund Manager of the Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund (SMEEF), notes how renewable energy developers often need to channel compensation funds — traditionally focused on seagrass, seabirds, and reef habitats — into credible, science-based interventions. SMEEF is already operationalising this model in Scotland by directing developer funds into marine restoration projects, such as seagrass meadow rehabilitation and seabird conservation. These initiatives provide a tangible route for private capital to flow into nature recovery, ensuring that industry obligations generate measurable ecological gains.

Finally, systemic change will require direct policy actions that reshape incentives across the global economy. Adrian Gahan, Ocean Lead at Campaign for Nature, points to three levers: removing harmful fishing subsidies, imposing a levy on fossil fuels, and charging usage fees for tourism and shipping. Each measure would create revenue streams that would fund ocean protection for those that benefit from it’s services.

Taken together, these methods reveal the breadth of opportunities to mobilise capital: from traditional grant and bond structures, to innovative de-risking assets, to bold fiscal reforms. The common thread is clear — investment in the ocean must be designed to align financial returns with ecological outcomes, providing stability and scalability for capital markets while accelerating recovery of marine systems.

Measuring marine environments: monitoring investment and tracking impact

For ocean finance to scale, investors need confidence that ecological outcomes can be measured in ways that are robust, comparable, and financially relevant. Monitoring is not just a scientific exercise but a core component of directing policy, managing risk, and demonstrating returns. As Max Boucher of the FAIRR Initiative notes, monitoring should be used to direct policy, ensuring that investment is guided by evidence rather than after-the-fact correction.

Eoin Murray of Rebalance Earth stresses that investors should “work and invest within the existing science guardrails, not wait for better science”. The tools we already have — from ecological baselines to biodiversity indices — can provide sufficient confidence to direct capital now. The key is making those tools usable for finance.

Methods of Measuring the Ocean

Modern marine monitoring combines traditional methods with scalable digital technologies. Benthic and mid-water communities can be assessed using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and camera arrays, supported by machine learning models trained to classify species and habitats. This reduces dependence on large research vessels, as Leigh Storey of NERC observes, but it also raises the challenge of automatic data processing at scale, especially when transferring models between ecosystems.

Structural complexity is another emerging metric: reef rugosity, habitat heterogeneity, and 3D reconstruction of benthic environments are powerful indicators of biodiversity potential. Given that structural complexity is a driver of biodiversity across scales, it is increasingly being used as a proxy for ecosystem health.

Alongside physical surveys, environmental DNA (eDNA) is transforming biodiversity monitoring. By sequencing DNA fragments from seawater samples, scientists can rapidly assess species presence — including cryptic or rare taxa — in ways that are scalable, repeatable, and relatively low-cost.

Metrics such as Mean Species Abundance (comparing an area of interest to a pristine baseline) and Potential for Loss (predicting likely biodiversity declines) are commonly used as indicators. Together with ecosystem service classifications (provisioning, regulating, cultural, supporting, as outlined by Klaas de Vos), these approaches frame the ecological “balance sheet” of marine systems.

A key question, raised by Roger Proudfoot of the Environment Agency, is whether there is a requirement for time-sensitive, real-time monitoring data. For some investors, annual or quarterly data may suffice, but for others — particularly in sectors such as shipping or aquaculture — up-to-the-minute monitoring is crucial for managing operational and reputational risks.

Standardisation and Disclosure

For marine monitoring to mobilise finance, it must be standardised. As Thomas Maddox of CDP highlights, investors need data that can be compared, aggregated, and translated into ROI for ESG reporting. Michelle Devlin of CEFAS adds that data must also be accessible and inter-relatable, bridging gaps between datasets collected for science, regulation, and finance.

Blanche de Biolley of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) outlines 14 recommended disclosures, organised under four pillars: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics. These disclosures encourage companies to systematically report nature-related risks and dependencies. Tools such as ENCORE (Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure) and TNFD’s LEAP (Locate, Evaluate, Assess, Prepare) approach provide practical frameworks for investors to understand how their portfolios intersect with natural capital.

Language and Translation

Even when data exists, the language gap remains a barrier. As Thomas Maddox notes, scientific monitoring must be translated into formats accountants and investors recognise, such as spreadsheets and ROI projections. Roger Proudfoot echoes this: environmental and conservation data needs to be re-expressed as investment-relevant outcomes. Gerrit Sindermann of the Green Digital Finance Alliance points out that marine data has not historically been collected with ROI in mind, which creates a disconnect between data holders and financial actors. Bridging this translation gap is critical to align conservation outcomes with financial returns.

Complexity of Data

The ocean is inherently complex, and marine monitoring reflects that complexity. As Gerrit Sindermann notes, investors often gravitate toward carbon credits because they are relatively straightforward: one credit equals one tonne of carbon avoided, removed, or reduced. By contrast, biodiversity is more difficult to measure and communicate, leading to a mismatch between ecological importance and financial uptake.

This is where concepts such as simplexity — making complexity navigable through simple interfaces — are valuable. As with carbon markets, the challenge for ocean biodiversity is to create accessible metrics that hide the underlying complexity without losing integrity.

Risk Management

Ultimately, measuring the marine environment is about risk management. François Mosnier of Planet Tracker stresses the need to convert scientific data into financial risk, a task that remains underdeveloped. For instance, although 75 ocean-linked corporations mention biodiversity in their reporting, but only 25 measure it. Without stronger disclosure, systemic risks will remain invisible to markets.

Frameworks like the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model provide causal clarity, linking societal activities (e.g., fishing, shipping, energy) to ecological change and economic impact. Applied at scale, DPSIR can help investors and policymakers see where interventions will mitigate risks most effectively.

Summary

Robust monitoring is not only a scientific necessity but also the currency of ocean investment. It directs policy, reduces uncertainty, and translates ecological outcomes into the risk-return frameworks that investors demand. By combining scalable new methods (eDNA, UAVs, AI) with standardised disclosures and translation into financial language, monitoring can unlock capital for ocean recovery. The task ahead is not to eliminate complexity but to manage it — making marine outcomes visible, comparable, and investable.

Philanthropy vs an ocean economy

Ocean conservation has historically relied heavily on philanthropy and grant funding, but this model is inherently limited. As Pernille Holtedahl of Imperial College London notes, philanthropic return on investment (ROI) is defined by principles or goals — such as protecting species or habitats — rather than financial outcomes. This makes philanthropy powerful for targeted interventions, but dependent on donor priorities and goodwill. Tim Morris of Associated British Ports observes that philanthropic donations “are reliant on good will, whereas a business-driven approach is sustainable through investment as a ROI is generated.” While philanthropy can catalyse projects, it rarely sustains them at the scale required to address the global ocean challenge.

By contrast, the ocean economy frames conservation as an investable proposition. Sustainability is not a by-product but a driver of financial value, achieved through de-risking supply chains, protecting natural capital, and ensuring long-term returns. Tom Brook of WWF stresses the need to move away from an attribution model of “we saved nature” toward a focus on de-risking and resilience. Decisions based purely on sustainability may not always deliver a financial ROI, as Holtedahl notes, but investors increasingly recognise that long-term ecological health underpins financial stability. As Adrian Gahan of the Campaign for Nature emphasises, sustainability cannot come from donations and grants alone — investors are seeking financially backed, scalable solutions that integrate conservation into market logic.

The ocean economy also requires professionalisation. While philanthropy often relies on volunteers and citizen science, Sarah Brown of the Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund highlights that “the ocean economy relies on skilled, salaried professionals.” Ensuring technical expertise and stable employment is essential for long-term stewardship. At the same time, communities should not be passive beneficiaries; they must be active participants in shaping and benefiting from ocean investment, embedding local knowledge and equity into decision-making.

Scale is a defining difference between philanthropy and an ocean economy. Torsten Thiele of the Global Ocean Trust points out that fishery subsidies still outweigh sustainable investment, showing that current financial flows are misaligned with ocean sustainability. Philanthropy alone cannot redress this imbalance, whereas the ocean economy offers pathways to mobilise mainstream capital — from private investors to sovereign funds — to generate sustainable, scalable, and financially resilient outcomes.

What’s next for the blue economy?

The next phase of the blue economy is not defined by a need for more funding, but by better direction and coordinated action. Max Boucher of the FAIRR Initiative notes that the sector doesn’t require more money; it requires clear pathways to translate existing resources into impact. The foundations are already in place: governments, investors, and institutions have developed mechanisms for sustainable finance, blue bonds, ecosystem service payments, and nature-based solutions. What remains is to deploy them effectively and at scale.

Thomas Maddox of CDP emphasises the advantage of acting now: “Don’t wait to invest. There are many different imperfect systems, but the direction of travel is clear. Acting now will give corporations a competitive advantage.” Early movers benefit not only from positive ecological outcomes but also from enhanced reputational, operational, and financial positioning. In a fast-evolving market, hesitation risks being left behind as others integrate sustainability into their core business models.

Dickon Howell, CEO of Howell Marine Consulting, echoes this sense of urgency, urging stakeholders to use existing mechanisms to make ideas happen, rather than waiting for perfect systems or metrics. Tom Brook of WWF reinforces the point: “Don’t delay action looking for the perfect metric.” In practice, this means leveraging current data, monitoring frameworks, and investment vehicles to implement interventions that can be iterated, scaled, and replicated.

Scalability and replicability are central to the blue economy’s potential. Torsten Thiele of the Global Ocean Trust stresses that interventions should be designed to facilitate replication and scale, ensuring that successful projects can expand geographically and financially. Frameworks such as the Crown Estate’s roadmap illustrate how goal-setting, clear pathways, and structured implementation can translate ambition into deliverable outcomes.

The blue economy is already demonstrating that diverse interventions — from sustainable fisheries, marine protected areas, and offshore renewables to de-risking assets like oyster reefs — can deliver measurable ecological and financial returns.

Ultimately, the future of the ocean economy lies in direction, execution, and scaling, rather than in further debate over ambition or funding gaps. By acting decisively with existing tools, investors, governments, and businesses can accelerate sustainable use of ocean resources, de-risk marine-dependent industries, and unlock both ecological and economic value at a scale that philanthropy alone could never achieve.

Useful publications

The role of MTRU research in a blue economy

The University of Essex’s Marine Technology Research Unit (MTRU) is at the forefront of developing next-generation tools at the intersection of AI, engineering, and marine science, offering transformative ways to monitor ocean ecosystems with unprecedented speed, accuracy, and scalability. Our research spans 3D imaging of coral reefs and coastal habitats, automated biodiversity mapping using deep learning, real-time environmental modelling, and advanced structural complexity assessments. By combining these technologies, we can produce high-resolution, evidence-based pictures of ecosystem health and change, providing actionable insights for impact assessments, adaptive management, and long-term conservation planning.

These capabilities are designed to meet the needs of the emerging blue economy. Investors, policymakers, and businesses require credible, timely, and standardised data to reduce uncertainty, de-risk projects, and demonstrate measurable returns. MTRU’s tools are explicitly tailored to support robust reporting aligned with ESG, TNFD, and other sustainability frameworks, translating complex ecological data into formats that inform investment decisions and corporate strategy.

If Blue Finance 2025 has inspired you, as it has us, MTRU offers a pathway to turn ambition into action. We are always keen to talk to partners, collaborators, and early adopters to test, apply, and co-develop these AI-driven monitoring solutions. As participants at the conference agreed, credible data is no longer a “nice to have” — it is the backbone of any serious blue finance strategy. By working together, we can ensure that investment, science, and policy are fully aligned, enabling scalable, measurable, and sustainable impacts for the oceans and the communities that depend on them.